academic journal access is a dog from hell

on trying to research a PhD application without the support of a university library, and McDonald's breakfasts, and being tired

From the age of eighteen to twenty one, I lived in a glorious dreamland otherworld where the streets were paved with gold and pain did not exist. That’s because I went to a university where cost and access issues associated with accessing academic material did not exist. Remembering that time now I feel like Eve looking back at the closed gates of the Garden of Eden. I was so innocent I didn’t even know I lived in a rare and hard-to-access best possible world.

Going to one of the richest and most well-resourced universities in the history of the world, there was nothing I couldn’t read. I could read every journal in every language, access everything ever published in the UK, and if there was ever a book I needed that was somehow not in my college library, a librarian would walk down to the academic bookshop at the end of our road and buy it or order it from Amazon for next day delivery. When I took a special option paper in medieval Welsh language and needed a very expensive, almost-impossible-to-get four volume dictionary of medieval Welsh, the library bought it. That optional paper was cancelled the year after I took it, and the librarians probably knew no one else would ever want the dictionaries or the complete works of Iolo Goch in the original Welsh, but they bought it all the same.

I’ve had a lot of conversations about the privilege that comes with going to One of Those Universities. There are a hundred potential conversations there, all of them leading to productive places for individuals and for society. I hadn’t realised, though, until I went to a very different university for my masters in my mid-twenties, how different studying looks when large parts of the academic literature on what you’re trying to write about Just Aren’t There for you. Doing my masters at a lower-ranked, more poorly resourced university (and then trying to write my PhD applications without a university affiliation at all) made me feel like I was navigating by the stars with my hands over my eyes, just peeking through the gaps in my fingers. I’d have an idea, look up what was available on it and go, ‘well I guess I can’t have that idea’.

The difference between my first university and my second was never the quality of instruction or calibre of teaching. The university where I did my masters had some of the best teachers I’ve ever experienced. The fact I had to work full time to make ends meet durng my masters whereas I could afford to live a classically gorgeous ‘life of the mind’ at undergrad was a big difference, but it could be worked around. The fact I couldn’t get my hands on research materials was something that was hard to work around. I often felt I was using all my capacity to have clever ideas for a day to get my hands on books and articles that used to just be there, then I had less time and brain left to have actual clever ideas about the material.

When people ask about the difference between the universities I’ve attended I think they’re often surprised by this being my main point. I think people are expecting me to say I miss being surrounded by elegant, non-job-having dark academia types in renaissance buildings. I can romanticize plate glass buildings and I can eve bring myself to socialise with people with jobs. I just want to be able to read the journal articles.

It got worse after I finished my masters dissertation. In my ‘gap year’ between my masters dissertation and the first day of my PhD, I’ve become what drop down lists on forms call an ‘independent scholar’. Independent here means not welcome in many libraries. I’ve been writing the longest and most complex application forms of my life with uneven patchwork of websites that let me read anything at all.

So in this essay I want to take a tour through what I’ve been reading and where, and how much this is costing me. I’m not intending this to be a ‘what I read in a day’ essay, though that might be interesting to one or two people. I thought it would be worth writing because I want to show how much time, effort and expense it’s taking me to get academic material into my eyes. I wish I could show this account to my eighteen year old self and make her understand how wonderful and worth being grateful for her situation was. I want to have this here to reread every time I wonder why I’m tired.

I should say as a quick note to begin with that my research is in a deep specific hole of the humanities. I write about British folk horror movies from the 1970s today, their medieval sources, medievalism more broadly, horror more broadly, and translation, adaptation and reworking of medieval texts reaching us in the modern day. A lot of the films I’m trying to work on, including David Lowery’s The Green Knight which was my masters dissertation, have only a handful of academic papers on them. Sometimes, as with this 2021 film, it is because it’s a shiny new movie that hasn’t had much said about it yet. With older movies like The Blood on Satan’s Claw or TV series like Children of the Stones, it’s because the academic establishment hasn’t produced a lot of writing about low budget 70s TV movies (alas). I’m often on the trail of the one article on a topic, or the three articles on a topic. My needs are narrow and odd. My strange patchwork of ways of getting books is, also, narrow and odd. This is where we end up.

London university libraries

I don’t have these. As an alumnus of a college of the University of London, I had hoped I’d be able to continue to use the main central library at Senate House. Unfortunately my university, Birkbeck (the UK’s only university organised around evening teaching to make studying accessible to people with work and complicated caring responsibilities) doesn’t qualify me for lifelong library access. I’m not sure what the reason for that is, but sure. My access to Senate House expired the day I handed in my masters dissertation.

I’ll be paying my deposits and getting my student card sorted at the university where I’ll be starting my PhD in October as soon as I can, but I’m not too optimistic about getting full library access before September or so.

Cost of access:

Nothing, but also no access.

archive.org

Archive.org is beautiful. It’s beautiful in every way a website can be beautiful. If I became a dictator and had the power to block and allow apps at will, it would just be Substack, archive.org and AO3 with a free pass to do anything they wanted forever.

When I started my masters, a friend who is also disabled told me it was possible to fill in a form communicating to archive.org that I have a disability affecting my ability to read print books and it would enable me to access more books on there. I thanked her but privately thought that was unlikely to work out for me. I’m never sure exactly how much I want to count myself as disabled. Sure, I have a mental illness the treatment of which is bankrupting me and a condition that’s caused a good amount of pain in my hands and wrists for the last decade, but I never wholeheartedly feel good about saying ‘yes, I am disabled’. During my undergraduate degree I was in enough pain regularly enough that I seriously struggled to type or hold a pen for longer than a few minutes, and I felt able to use the label then, but that level of pain is very rare for me now. I went to fill in the form more because I wanted to be able to tell my friend I’d taken her advice than because I thought anything would come of it.

I should have had more faith in the beautiful people at archive.org. I not only got accepted for disability access, the whole process was simple and, dare I say it, even a little bit dignified. That gets me the right to borrow full searchable ebooks of a lot of academic books. They’re usually slightly older ones, but it’s got a good selection of Key Big Texts in full for a lot of literary theory and criticism. It’s where I read my Bakhtin and a lot of gorgeous books of anthropology and Middle English analysis that I used for my masters dissertation. It’s how I got through Bakhtin’s The Dialogic Imagination and Svetlana Boym’s The Future of Nostalgia. There’s very good stuff on there. It’s not good for recent stuff and the access is spotty among older things, so similar to JSTOR it can’t be fully relied on, but still, lovely.

If anyone is reading this and thinking ‘I’d love to be able to read those kinds of things but I’m not sure my disability will count’, I really strongly recommend you go take a look at the form. Who knows, you could end up in the Bakhtin fandom with me.

Cost:

Free, just a gentle kiss on the forehead for every employee of archive.org that would like to accept it.

The British Library

The British Library is the UK’s national library. Access to its reading rooms gives you, in theory, access to request books from its vast physical holdings and also to look at digitised manuscripts and other academic materials. It’s a valuable resource that anyone in the UK can use. Unfortunately, at the end of 2023 it was the victim of a vast and devastating cyber attack which pretty much turned all its computers into expensive paperweights.

Access to different parts of the library’s collections and functionality trickled back slowly, in a horrifying illustration of how much damage a well-placed cyber attack on an underfunded public good could do. I attended classes, lectures and conferences where people’s slideshows had blank gaps where screenshots of manuscripts were meant to go. Where a lot of free-to-access manuscript scans were meant to be, there was just a hole.

For most of the time period this essay covers, the British Library could only really be useful to me as a study space. I did like and use it as a study space. For most of summer 2024, me and two friends from my masters course would do full day shifts there. The wifi was back and the cafe was in existence, which was all the resources we really needed it to provide.

They were good days and I loved studying there. The fact the British Library is free and open to everyone is a fantastic thing, but it hasn’t been able to get me access to much and it also hasn’t been completely free to me. It’s great to have a study spot to meet my friends and use large well-lit desks, but man cannot live on desks alone. Sitting in the British Library with stuff to read is great. Sitting in the British Library without stuff to read is just a chair and a nice skylight.

Cost of access:

Being in the British Library for a full day of work means getting there as it opens, which means getting there on the train during the most expensive peak hours on London public transport. For me that works out at around £7 to get there and back. If I turned up later I could save money by travelling off peak, but the reading rooms close at the end of office hours so you aren’t getting a full day of work in if you don’t arrive til lunchtime.

It is of course possible to be somewhere for a full day without paying for food or drink, but I can’t realistically do it. I have quite strict and weird feelings about eating lunches that haven’t been in the fridge, so if I were packing a lunch I could leave in a locker at whatever temperature all day it would just be granola bars and crisps etc. Maybe I should try and do that, but in practice I don’t. Particularly when I’m there with friends and we’re wanting to eat together, I end up paying for a coffee first thing in the morning between the building opening and the reading rooms opening, and something for lunch. We usually stick to fast food and I only drink plain black coffee, the cheapest thing on any coffee menu, but we’re likely looking at a further £8-10 minimum for the day.

Total: £15-17 per day.

JSTOR

Being an Oxford alumnus comes with a lot of benefits that I didn’t realise would come to be so important to me. One of these is lifelong access to JSTOR. JSTOR, my darling, I didn’t understand when I was younger how important you would be to me forever. I took you for granted and I’ll never do it again. We belong together.

JSTOR is wonderful but not perfect. There are journals I like and use a lot which are there, such as the Chaucer Review which I love to click about on and open random articles that make me go ‘ooh’. It’s great for older papers and understanding where terms and methodologies started and grew from. It’s not, however, the case that every single article I ever want is there, or that I can learn about every topic equally. I’ve found it better as a browsing place than a place that I can look for something specific and trust it to be there.

In order to use JSTOR, I have to log in through a separate alumni account site, click through to JSTOR and then search on there. It logs me out every few minutes and I end up with fifty tabs in a wild and beautiful constellation across my browser. That’s a small issue to complain about when I get access to journal articles for free, something not a huge number of universities fund for their alumni, but it is annoying.

Cost of access:

Free.

Going to Oxford

As an alumnus, I have the right to turn up in Oxford’s Bodleian library and work there. To get that access, I had to fill in the same form any non-university-member would have to fill in to get access, including writing a personal statement about what I wanted the resources for, what specific texts I needed and how I’d tried to get them every other place I could. I had to print that form and bring a couple of forms of ID and a printed bank statement to the offices in the Weston Library so that I could get a library card. Being an alumnus, I’m pretty sure they didn’t squint too hard at my written statement, though I can’t say how far that’s the process for everyone versus just how my office worker treated my form on my day. I got a year’s access for free while non-alumni have to pay for the card and only get to access it for a predefined length of time, for example the exact length of time they’ll be in the city for a conference or project.

When I’m sitting in an Oxford library and connected to the university wifi, I have full access to all the library’s online resources. That means that if I’m sat in the library I have no difference between what I can access and what the current student sat next to me has. The only difference is that once my laptop disconnects and I go home, that all vanishes.

Going to a beautiful city to sit in a beautiful library and download as much free material as I can cram into my iPad isn’t a bad way to spend a Saturday. The only reason I’ve not done it more than once so far is that, even with the free library card, it’s an expensive and exhausting thing to do. Being there for the full Radcliffe Camera opening hours means waking up at my flat in London at six in the morning and travelling for two hours, spending an average of around £40 on trains. It’s spending ten to twelve hours out of the house on a Saturday when I’ve just worked my full time job Monday to Friday. Which is fine, I can do it, and I love spending my weekends on the academia stuff I’ve been looking forward to all week. Doing a full week of work then setting an alarm even earlier than I did for the office to go to a library is hard on the old brain though.

Then we’ve got the same issue as when I go to the British Library. I’d love to say I got up earlier than I needed to to have a filling and nutritious breakfast before getting the train and I took backpack-stable granola and fruit to Oxford with me. If I were a better person I’d do that. But it’s more like a McDonald’s breakfast to help me maintain that will to live and then crawling away from the library towards something warm for lunch with a coffee to try to drag my neurons forwards towards the end of the day.

I try, I do try, not to waste money on coffee out when We’ve Got Coffee At Home. I don’t buy coffee on work days and I’ll take a free coffee over a paid-for coffee no matter how much like stagnant pondwater it is. But if I’m away from home with no access to free caffeine for that long on a Saturday I’m paying for it. I just am. I have no aspirations towards home ownership anyway. It’s fine.

Cost:

£40ish on trains getting me across London, to Oxford and back. It looks like less than this when I check the prices for next week but I think this is about what I paid last time.

£15ish for breakfast, lunch and coffee. Don’t tell me I’m a bad person for this. I already know.

Perlego

I’d seen Perlego advertised on a bunch of YouTube videos and I scrolled past it, because of a deeply-held and general belief that YouTube has nothing good to sell me. Then I heard about it from my friend Charlotte, who is an actual human person, and I went, ‘I didn’t know that was something actual human people use’. And she said, ‘yeah, it’s pretty good’.

It’s a site you make an account on, costing £9 a month, with a pretty lovely library of academic texts. It advertises itself as a source of textbooks but there’s a lot there beyond undergraduate-style textbooks. The experience of using the site is lovely, the highlighting and annotation features work really well and I’m finding it intuitive and elegant to use so far.

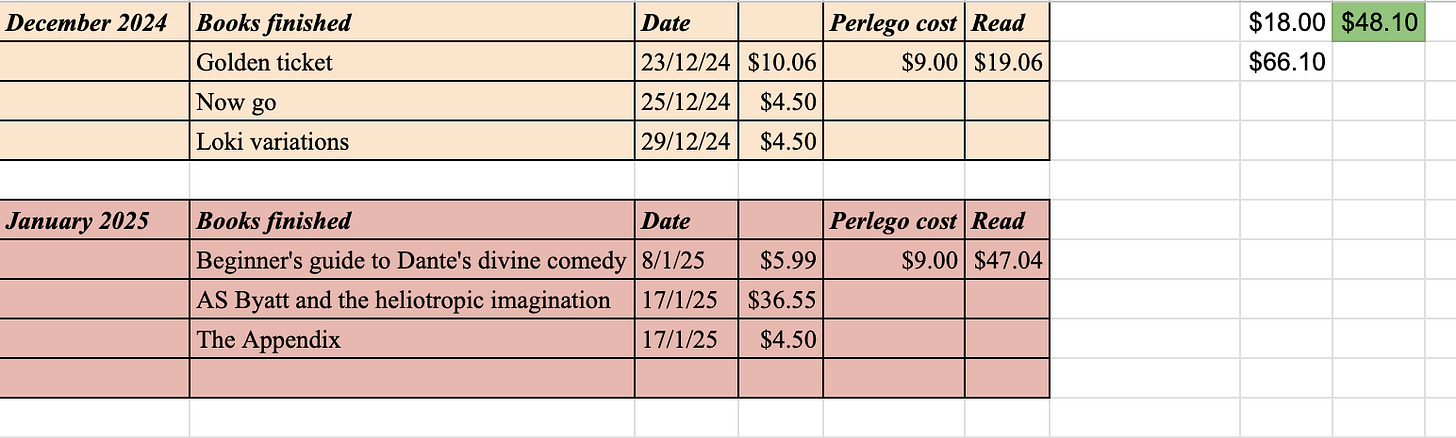

Having a subscription to a paid account like this does make me nervous. I’m haunted by the idea of absentmindedly paying for a subscription for years and realising later I’ve spent £200 on something I’ve never used. Hence, my spreadsheet.

My continued use of Perlego is dependant on this number on the far right of the spreadsheet staying green:

(Ignore the fact it’s all in dollars. I can’t work out how to tell google sheets my currency is in pounds.)

I’ve been adding up the cost of how much the books I read would have been if I’d bought the ebook on kindle on the day I got it from Perlego. I don’t know how long I’ll be using it for, only the spreadsheet does, but I do have a long TBR list on there of books relevant to my PhD as well as a few other ones for my ‘gap year’ of things I’ve always wanted to learn more about but couldn’t justify academic book prices for when I don’t even study them. It feels pretty good to have downloaded a book about eighth century Chinese poetry and be able to read and take notes on it without having paid for it, or at least, without having paid for it in its own right separate from the subscription.

My only real worry is that this will lead to an outbreak of me paying for things YouTubers told me about. I’m terrified for the future of my mattress.

Cost:

£9 per month, my dignity.

The London Library

The biggest investment on this list is me joining the London Library. I’d never heard of it before this Christmas, or rather, I think I’d heard the name but assumed it was somehow affiliated with the British Museum. I have no idea where I got that from but I know for sure that when I read the opening chapters of A.S. Byatt’s Possession, set in the London Library, I was always picturing the British Museum. Go figure.

My partner told me about the London Library in the form of offering to buy it for me, and I’ve got to say, that’s my preferred way of finding out about everything. I think he knew how much buying books individually and waking up at six to get trains to Oxford was shortening my life. The London Library was presented as a solution and while I don’t know if it’s 100% of a solution, it’s pretty damn good.

The London Library is a private academic library near St James Park in one of the prettiest and most old money dear-god-why-won’t-a-duke-just-marry-me parts of London. It has three townhouses’ worth of stacks and beautiful reading rooms, gorgeous online resources and subscriptions to every publication of the literary press in the UK and America that I can name. There are a lot of ebooks and audiobooks you can download through Libby, and the online academic material uses a similar operating system to Oxford’s online holdings. I’m not sure if it’s just my familiarity that makes it feel easy to use, but it does feel very intuitive to me. Going there for the first time made me exhale with relief, a feeling like, ‘ahh, I can calm down now’.

It’s wonderful but there’s a good amount to say on the cost.

A young person’s membership is around £26 per month, where a young person is defined as a person age 29 or under. In a year’s time when I am no longer young, it would be £50 per month. You must join the library for a minimum of a year, which means committing to the membership is promising to pay just over £300 total. You have to trust it’s going to be worth it, and you’re going to be able to make it worth it, at the point you sign up.

My boyfriend volunteered to pay for a couple of months and my parents liked the idea so much they said I could have six months of library as a birthday present. The fact everyone was so keen to pay for this makes me realise something about how much I’d been complaining about this to begin with. I’ll end up with about £100 to pay at the end of the year in the post-birthday-gift world.

And naturally, I have a spreadsheet tab for this:

I’ve only been a member for a couple of weeks so I’m still recouping the first month’s cost, but I’ll be staring at this tab hard this year to try and keep my usage of the library resources above £26.55 per month, across both physically spending time there and using their online resources for academia and for pleasure. I’ve heard rumours (that I haven’t checked out yet) that there is free coffee and fridges for lunches available on the top floor. Be still my beating heart.

I’m intending to do one or two evenings there after work on the weekdays they have their late opening hours. That will mean I’m out of the house from 7.20am to commute into work until 8 or 9 at night, but I’ll get to lay eyes on a lot of books in between. When I have nothing on at the weekends I’ll try to go on Saturday mornings to pick up books and maybe read the Times Literary Supplement if I’m feeling really bourgeois.

Is the London Library something I’d recommend? Sure, if you’re age 29 and under and have access to either £312 or loved ones with disposable income who are sick of listening to you complain. I’m lucky I have that, and I’m lucky I’ve found a good patchwork solution to help me cover the ‘gap year’ gap between masters and PhD. I know there will be a lot of people this doesn’t work for, either for cost reasons or because getting to St James Square isn’t going to work for them regularly.

Cost:

£312 for a calendar year, which is the shortest term you can sign up for. If you are unfortunate enough to be over 29, it will be £624 for the year. That’s a lot.

Conclusion

I don’t know what the conclusion is here. Have I got a good situation going now for academic access? Yes I have. I can read not quite everything but a good number of things. I reckon my conference paper on Dante and social media medievalism for July is going to get written and have a respectable bibliography. I reckon I’ll turn up at King’s College London with a respectable amount of reading done. I think, for me, it’s going to be okay.

Getting that sorted has required only: being an Oxford alumnus, several hundred pounds’ worth of subscription payments, taking some trains, being disabled, colour coded spreadsheets on the economic returns of different libraries, and writing several personal statements and letters about how disabled I am and how much I like books. No individual reading this is going to be able to recreate every one of those steps. I’m still very priviliged and also, still, very tired. I’m in a better position than a lot of other people.

Ultimately I don’t think there’s a way to collage together an individual solution to the issue that getting access to academic materials is hard. It’s hard when you’re not a member of a university and it’s hard when the university you’re a member of isn’t one of the UK’s top most prestigious well-resourced ones. It’s hard if you don’t live in London. Multiple times in the above sections, I was reliant on other people’s help whether it was literally paying for things for me or just them having heard of things I hadn’t, keeping a look out for things that might work for me, having their own experiences of being disabled students in the humanities in constant search for books.

The only solution that would make a real difference would be to make more academic materials available to the general public without gatekeeping according to institutional affiliation. It makes sense on some common sense levels to have access to academic materials determined by your university - universities are where we read big books mostly - but in the twenty first century, more and more people are having gaps between degrees where they save up funds. Getting back into academia after a break is hard.

If it’s been hard for me, an Oxford alumnus living and working in London with money to spend and goodwill among my friends and family who recommend me solutions and pay for things, what's it like for someone with no connection to Oxford, living a good distance from a large university town or the UK’s centralised resources? Could that person write my Dante paper for the conference in July? Could they arrive for their PhD having done a good amount of pre-reading? Could they indulge in a passion for Tang dynasty chinese poetry? Probably they could, but they’d have to be more resourceful than me and work harder than me. They’d end up more tired than me. I’m pretty tired.

this is a very useful post

Thank you so much for this information about archive.org, I’m going to look at the form and see if my disabilities count. (If it does, you might just have saved my life!) Academic access is such a difficult thing. I’m in a French university (and not one of the big Parisian ones) so I have access to a few things but not to any UK or US based website, which means I miss out on most resources written in English, and they’re often the only things that exist on the topics I research.