phd preparation diaries: the real academia was the friends we made along the way

on connection, academic friendship and getting my phone stolen (but make it academia)

Thank you so much to my paid subscribers who make everything I write here possible. That’s doubly true for big translation and commentary projects like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which take a lot of work and will all be posted for free. If you’d like to read more of my writing and support my work, you can become a paid subscriber for £4 per month and get an extra essay per week. Coming up soon we have medievalism in Elif Batuman’s The Idiot and medievalism in Call Me By Your Name. If you would like to support me but aren’t able to become a regular paid subscriber, I also have a ko-fi tip jar here.

On Monday night this last week, I went to my friend Rose’s house for dinner and we talked about what the theme for the next issue of the PhD preparation diaries would be. I said I was excited about writing it and it was an issue she was going to feature heavily in. She said ‘ooh’. I said I wanted to write about academic community and how academic community is kind of the whole point of all of this.

On my way home from that dinner, I was a victim of one of the random phone snatchings by guys on bikes that people talk about more and more in London. I’d been hearing about them for years, but I didn’t think of them as quite a real thing that was going to happen to me. Did I have my phone out? I did, and I know it’s not what anyone’s meant to do, and I won’t do it again, and I’m sorry. I was on my own street, where I know the names of my neighbours, within sight of my flat, somewhere I’ve lived for years. “I just didn’t think it would happen to me,” said everyone that anything bad ever happened to, but I just didn’t think it would happen to me.

In lots of clear and obvious ways, I was lucky. The interaction was over in probably less than four seconds. There were two guys, one of whom didn’t come near me, and the guy that did come near me barely touched me at all. I guess he touched my fingers a bit as he grabbed my phone but he didn’t put his hands on me in any meaningful sense. Did it feel like a violent act? Yeah, but I know someone who got beaten up by guys who took his phone.

The two images I’ve been left with stamped on my brain like weird traumatic 5D smell-ovision snapshots are a really big hand, coming out right in front of my face from slightly above. There was a fraction of a second where it felt like I was being scooped up by a big hawk or an angry god. I remember the palm of his hand was very pale and having a weird ‘that’s a really pale hand in this light’ thought. I remember the back of his tall, skinny, slenderman-looking body cycling away in front of me while I shouted and started hyperventilating, and how the air felt oddly warm, and I remember the feeling of the air hitting me while I half-heartedly ran and breathed oddly. It was horrible but it could have been worse. I was not scooped into the sky by an angry god or a big bird.

Is the guy who took my phone a scumbag? It feels that way to me. But at the same time, I’ve believed for years that crime, particularly this kind of non-violent or barely-violent crime, is a social epidemic and people who swipe not-that-valuable phones like mine to sell for parts on a push-bike on a Monday night probably don’t have the best lives.

The real horror was walking back to my flat to tell my boyfriend and working out all the administrative issues I was about to encounter and what they’d cost. I spent the next however many days in kafka-esque admin hell, dealing with the fact I couldn’t get into any of my banking apps without an SMS activation code, but I couldn’t get a text without a SIM-card, and I couldn’t get a SIM-card because my account with my phone provider was locked due to me trying to log in and see my options for getting a new phone. The phone itself was an iPhone that I’d bought outright, brand new from an Apple store. I bought it with £700 I’d got from a family member with the idea that owning a phone outright and nursing it through until it died coughing up blood in its old age would save me money on monthly bills. That was barely a year ago, and my ‘investment’ started to look quite silly as the guy cycled away. I got the insurance option that covered me dropping the phone in the bath but not it being stolen. It seems I had more faith in other people than I had in me.

So it’s not been a great week, and it’s not been a very academic week. When you borrow a colleague’s phone to spend what feels like hours on the phone with your bank, hearing about how you have zero options for accessing your current account, doesn’t put you in the mood to think deeply about symbolic ecology. I spent most of this week unable to face working. I pretty much just felt very nauseous.

My original essay idea on academia and community also started to feel a bit silly. I didn’t spend much of this week feeling very linked to my community, the community in which two guys on bikes are still riding around.

I decided to write it anyway, though. I think the thing I’m going to look back on the most from this very shitty week is how kind and supportive people around me have been. Some of those people have been literally near me in my meatspace life and many more have been here on substack. I won’t rehash my gushing gratitude here, both for the people who sent me tips on my kofi account and for the people who commented and told me the same things had happened to them, and it’s okay, and I’ll be alright. I’m running out of ways to say thank you to people when everyone has been so kind.

My boyfriend ran out into the street when I got home crying to see if he could see the bike guys and get any information for the police, then he came back inside to give me hugs and help me fill in police and insurance forms. When I didn’t know when I’d get access to my current account he said he’d pay both our rent this month so I didn’t have to worry about it. I had to reach out to friends on email, like it was 1991, and tell them why I was ghosting them on whatsapp, and they sent me emails with titles like JAIL FOR PHONE THIEVES FOR A THOUSAND YEARS. My CEO told me to take however long I needed in the office to call my bank and said my work would get done when it got done. My parents read my freaked-out messages and sent calm replies in shifts.

I don’t think this experience is altogether separate from academia, though it doesn’t involve much reading. I read Ice Planet Barbarians for escapism while all this was happening and I’ve got to say, it’s better than you think. I am thinking of doing an ecological reading of the series.

I’ve benefited from having a community around me more this week than most weeks of my life, so we’re going to do the original essay I had planned.

The real academia was the friends we made along the way.

During my undergraduate degree, I certainly liked talking about the work/reading I was doing and the tutorial-based teaching at my university suited me down to the ground. I’m a very chatty person (you can tell from how I publish about ten thousand words a week about my life on here). I don’t think I understood, though, how much academic community really meant. I was the only person at my college studying my degree. I made some friends doing my degree at other colleges when we came together for shared classes. One of those people is Rose who cooked me dinner at the start of this essay and whose maid of honour I was earlier this year. Another was Georgia, who was two years younger than me, messaged me on facebook to get my old essay notes and continues to eat Korean food with me while we speculate about Reputation (Taylor’s Version). In general, though, I did my work in my room and I didn’t take extra opportunities to get in rooms with people and talk about the work.

It feels silly now, and my teenage self was silly, but I felt like I had so much on my plate with the work I didn’t have time to do ‘optional extra’ things. Lectures for my course were optional and I preferred to use the time reading. My university had more discussion groups, writing groups, additional talks, and opportunities to get coffee with people who loved weird niche things than anyone could attend in a thousand years. I just didn’t go to them. I was too busy texting people about how busy I was when I was actually just watching House in my underwear. Most of my literature-related memories from my undergraduate degree are just me hunched over books in my room or the basement of a library. Now I watch video diaries and read substacks of people studying there today and they say all kinds of things like, ‘Today I’m nipping into another college’s chapel to hear an early modern sermon performed with the original music with a few close friends’. I think damn, what was I even doing?

Towards the end of my third year, I had a flicker of realisation when I started a revision group for five girls in my year. (We were the only five on our strand of the course, so boys weren’t excluded, they just weren’t into manuscript studies). One of those five was Rose. The group was called Tea and Troilus. Over the course of however many weeks we worked out way through the whole of Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, which was our Middle English commentary text. In the exam we were expected to write a commentary about a short section of the text taken from anywhere in the eight-thousand-line poem. In my third year I did well on my college accommodation ballot and had a two room set with a bedroom and a neat little sitting room, looking out over the front quad spring flowers. I served Bird and Blend tea from my little salmon pink teapot and we sat in a circle around my coffee table, on the floor, because I only had two chairs.

Looking back on it now, I think it’s insane and kinda sad that I got most of the way through my final year before realising sitting in a circle on the floor drinking tea and laughing at Troilus was actually the whole entire point. Perhaps going to a university where there was infinite opportunity for discussion and community made it feel like I didn’t need to grab it because it would just be there anytime. I graduated and realised I missed it immediately. I was like a neglectful husband who realised how much my wife had really done around the house after she walked out.

In the five years I had between my undergraduate degree and my masters, academic community was the thing I most missed and wanted. I worked at a theatre that had a higher education research wing attached to it, and I’d slip into the back of workshops and lectures on restoration comedy rewrites of Shakespeare plays. I knew nothing about restoration comedy rewrites of Shakespeare plays, and I still don’t, and I didn’t speak, but I liked being there.

It became very clear to me that there was no amount I could read on my own on kindle on my lunchbreak that would go any of the way to replacing being part of an academic community.

That’s something people say about English literature degrees a lot. They say it slightly less about medieval literature degrees, because everyone knows Anglo-Saxon is hard, but there’s still a general belief that engineering needs to be done in a classroom with other people and an instructor, while an organised education in English is a ‘nice to have’ that could also be accomplished by reading books on your own in the bath. But I spent five years reading books on my own in the bath and it was so clear that something profound and important was missing. I could read and think a lot but I had no direction, no awareness of my gaps and blind spots, and nothing I read was ever able to turn into anything. It was unsatisfying in the way going on a lot of first dates and no one ever texting you after is unsatisfying.

So when I got into my masters degree, I was clear that I wanted very much to be part of any community at all that anyone had going. I wouldn’t say I was pushy exactly, but if someone made a noise that suggested they might want to go to the pub, I would ask every single person in the class if they wanted a pub trip, at any pub, at any hours, on any day. I was pretty close to handing out children’s birthday party invitations to everyone I met. I set up a reading group, and when a friend asked if I wanted to go to a one off session on memory and gender I said, ‘I know nothing about memory and gender, but sure!’. I attended every extra lecture I could, and I bought books by faculty members that were about the wrong periods and in one case the wrong continent. The reference one professor wrote for my PhD called me ‘invested in academic sociality’, which I hope was meant as a compliment. I set up the group chat for everyone writing dissertations in my year and set up writing trips to the British Library. If you were writing about anything medieval within ten miles of me, it became inevitable that you would come to the British Library with me.

I’ve written a bunch before about how my second university was very different to my first one. It was smaller and lower budget. What my first university had going on in two weeks was probably what my second university had going on in a year. But being older, and everyone around me being older, meant we all valued and invested more in what it meant to be there. We’d all spent a while out of academia, some of us one year and some of us fifty, and knew why coming together in a group for academic discussion, really together, in a room, mattered so much. I can honestly say I took everything the university had to give me. It feels like laying to rest the old ghost of a useless teenager who didn’t know what she had when she had it.

Many of the best memories from my masters are memories that feel like descendants of that Tea and Troilus group. Some of the things I think I’ll remember most include:

the breaks we took in our module on women’s writing, where the professor insisted we all go outside to smoke, and didn’t believe us when we said we didn’t smoke, so we’d all go down to the ground floor and stand on the pavement for five minutes, not smoking, and go up again.

my first academic conference, in a room that looked out over Oxford in the spring, and going to the pub afterwards with people who wanted to ask me questions about Tolkien and my PhD plans.

sitting outside the British Library on sunny days for lunchbreaks, long lunchbreaks, in the middle of dissertation writing, summarising our arguments to each other in the silliest words we could.

sitting in pubs and noodle bars with my favourite professors talking about werewolf movies and everything bad happening to modern humanities education.

And academic community spills over into so many other places. I have had to break away from writing this essay because my friend Mary from my masters is messaging me about Ice Planet Barbarians, the great epic of our times. I also had to take a break to tell my boyfriend, a historian I met at undergrad, about the cool lens on land and legality I’m learning from By the Fire We Carry. When I went to Rose’s house for dinner this Monday (a great dinner, though a big part of me wishes I hadn’t gone, or I’d left earlier, or stayed overnight, or something), I took a pouch of tea from the same place I got it when we did Tea and Troilus.

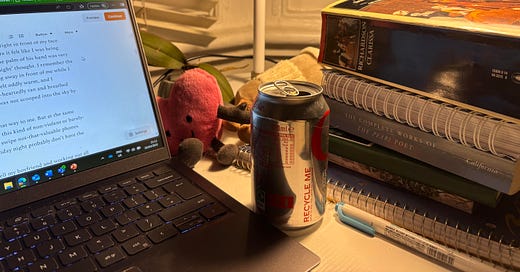

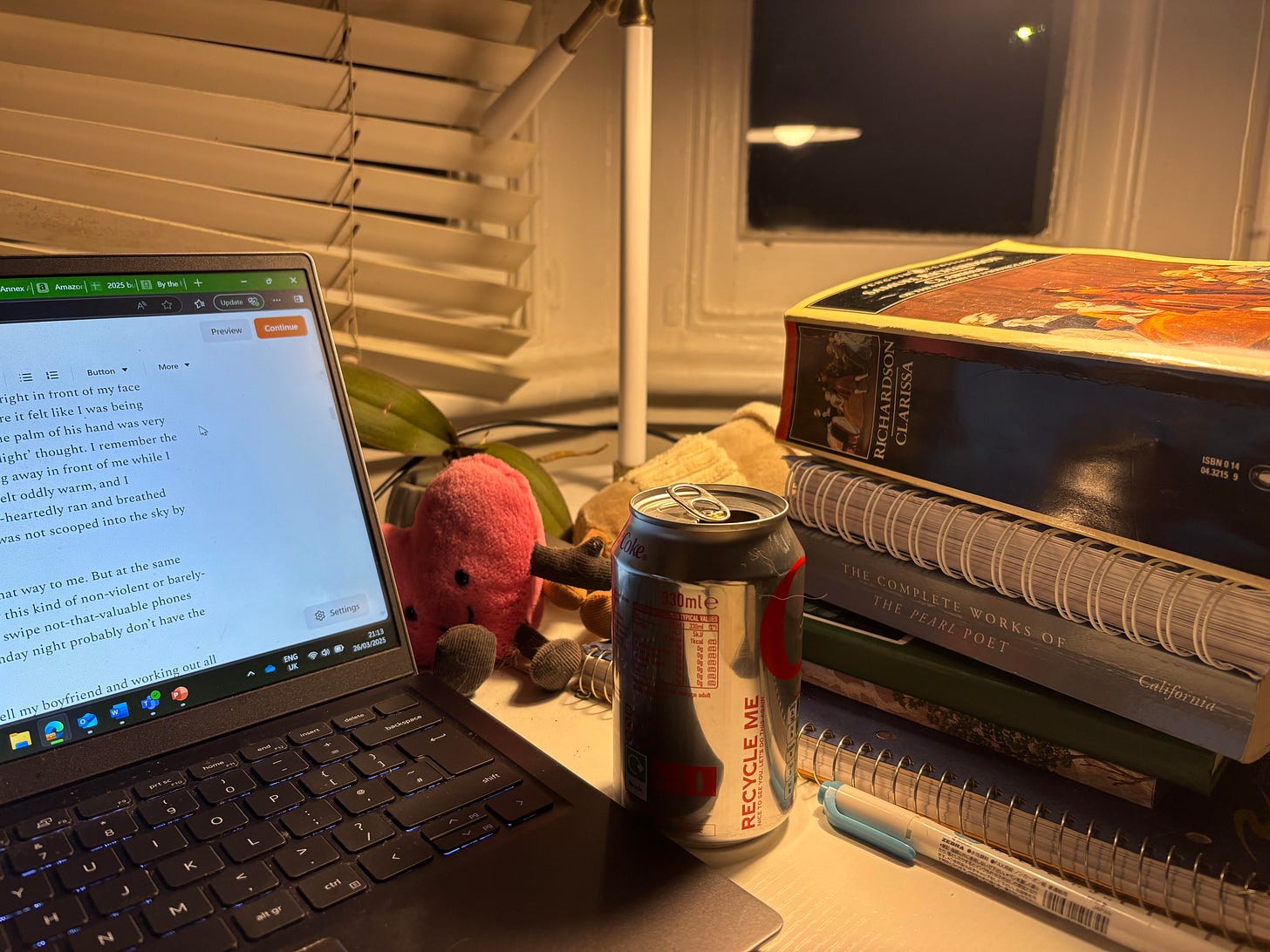

Going into my PhD, which I’m starting at a university where I’ve started turning up to academic events already, I know how much this matters to me. It matters to me around all the actual books on my reading list or the fact I have a job and a cat to feed. I learned exponentially more in two years of a masters degree done alongside other people and in dialogue with them than I did in five years of reading books in the bath. The humanities are able to really soar when they’re talked about, shared, and turned over in our hands together, passed around at a table, at a dinner, at the pub.

The first universities in the British Isles were founded around the idea of scholars sharing a table together in a hall. I think about that idea when I’m trying to plan a meal for five part time grad students with conflicting schedules, kids to look after, shifts in bars to work. Having classes in person together to talk matters and walking back to the station together afterwards matters too (sometimes I walked to the wrong station and had a ninety minute commute home for this reason).

Having professors there to talk to, formally and informally, deepens everything and makes it all so much better. It makes it better in a way that those of us who have tried to do without it understand deep in our bones. The professors I had in my masters did so much more than hand me reading lists and recite lectures over old slide decks. Talking to them made it possible for concepts I’d read about on my own to go from fuzzy and abstract to meaningful and concrete. Putting my own work into words in front of them and watching their facial expressions was an education. No matter how old I get or how expert my supportive friends say I am, I just love sitting in a room with people that much cleverer than me. I feel the same about my PhD supervisor. I like listening to him, sitting in his office staring at his bookshelves and trying to absorb all of them by osmosis. I sit in those meetings and know that in five years’ time, they’re going to have made me into a different person.

Big cheeses, movers and shakers want to remove funding from the humanities, here in the UK and abroad. I think a lot of them believe it doesn’t matter if you defund the table people sit at, as the books are still for sale and people can buy them on Amazon if they choose to. My life lived inside and outside academia has proved to me over and over again how much being together with other people to do it matters. In the funding situation we’re heading towards, it may be that medievalists like me end up having to do these things outside the academy, or online.

I don’t mind doing these things in a different form, as long as we do them. I love substack - I love having a text-based platform where people can write long, multi-paragraph comments in response to an essay that took someone hours. I like it in all circumstances other than me getting a five-paragraph comment about how fascism was good, actually. I like that everything I see on substack demonstrates to me peoples’ capacity to reach out and find each other when the real-world structures around us make it difficult. I want to fight to keep real-world academic spaces available for us but I also want to embrace the things people invent instead. I don’t mind multitasking.

I think of all you guys on here as part of my big multi-decade Tea and Troilus continuum. But some of you will have to sit on the floor. I don’t have that many chairs.

I think my favourite genre of Substack post is academics in humanities talking about how much they love other academics in humanities. It feels a little saccharine to say but I do truly believe that the way forward must have at least something to do with sitting around and talking about books.

I’m an undergraduate literature student, and a very introverted one at that. I often find myself frustrated with and isolated from other students in my cohort because it can feel like they don’t see the value in their degree or the books they’re reading and I wonder how it’s possible that these people can be spending SO much money to be here but if you ask them why they’ll just shrug. It’s pretty easy to slip into pessimism when everybody around you is constantly stressing about whether they’re getting their money’s worth.

However, there are also moments when I feel so, so proud of the students and academics that I get to work with. I was sat in a workshop yesterday listening to people talk about their dissertation topics and the room was suddenly brimming with enthusiasm, it was genuinely as though the sun had come out and you could see it on everybody’s faces. And I have been attending this Divine Comedy reading group throughout my degree; it’s taught by a wonderful retired professor in her living room and we all huddle around her on mismatched furniture and take it in turns to read the poem in Dante’s Italian (even though one in ten of us speaks a word of the language) and then she translates it live and explicates every reference for us and answers all our questions. The reading group is so popular that she now runs three simultaneous sessions a week. She doesn’t have to do that, nobody’s paying her, but she does it anyway. She’s my absolute hero, and when I read about other people like her, like you, pushing for ‘academic sociality’, it makes me feel a whole lot better about the future.

Sorry to hear about your London troubles, that place scares the bejeezus out of me, and sorry also for this very long rant!

Lovely! I couldn’t agree more on the importance of the community. We older people gather in book groups, but it would be nice if they were more age-mixed. At 64, I’m the youngest person save 1 in all of my book groups.

I also had my phone stolen once, but the nice thing was that the thief’s ineptitude allowed me to catch him (although I had to buy a new phone first, so this was not an economic benefit). Turns out he had accidentally taken a photo of his feet with my phone, which showed up with geolocation information in my cloud photo account, which I looked through with the new phone. This allowed the police to go after the thief, who returned the phone. May your luck be as good as that!

Anyway, I’d be grateful for eyes on my Substack, as I’m just beginning. It’s called The Duck-Billed Reader.