there's an only child weeping at the grateful dead concert

temporality, melancholy, handlebar mustaches

I don’t think I’ve ever written about music on this account before. The reason for that is that I don’t think I’ve got many opinions about it anyone would want to hear. You know that statistic about how 90% of people think they have better music taste than average? I attempt to buck that trend by being one of the people who knows my music taste is not winning any prizes for originality. I went to the Eras Tour three times. I love Hozier and Phoebe Bridgers. Sometimes I think ‘ooh, I’m being a bit interesting’ when I play REM or Joni Mitchell, then I remember they’re not actually underground acts no one’s ever heard of.

So don’t worry — this essay isn’t going to be one of the many acts of swiftie literary criticism I send my friends in long un-asked-for text threads. This essay is about the Grateful Dead.

It takes people by surprise a lot when I tell them how much I love, and how much I know about, the Grateful Dead. They see my general vibe and say, ‘really? — and I don’t think this is a manifestation of sexism at all. I think I really profoundly don’t give off Deadhead energy.

Music has always been the language I use to talk to my parents. I keep this part of my music taste (their music taste) in a separate part of my brain to Gracie Abrams and Noah Kahan, and you can know me for years and not meet it. I’m an only child. I get on great with my parents. At the grown up age of twenty nine, with a partner I’ve lived with for years and a full time job in London, I regularly turn up at their house for a long weekend to save money and eat whatever I can find in their freezer. That desire comes partly from budget-consciousness but largely out of love. We meet all the stereotypes of being a ‘three musketeers against the world’ family, a three-person Gilmore Girls with all the pop culture references and fewer bizarre emotional schisms. I know all their anecdotes off by heart, and the stories behind all the framed Roger Dean art above the dining table, and about how the first time my dad met his mother in law she hid upstairs because she could hear the drum solo from Moby Dick playing in the car and she thought a shoot-out was happening.

After we realised we’d done every vaguely Grateful Dead or even olde-worlde-music related quiz on the entire internet, we started improvising sprawling new games. Classics include me just opening a copy of Deadbase (the setlist catalogue with dozens of volumes) and coming up with setlist questions, or the bizarre ‘Guess the Genesis song but you can only ask questions about the circumstances of the lyrics’. On New Year’s Eve we make medium-quality Mexican food and time a Grateful Dead live DVD to finish at midnight, so I can experience a little bit of a classic New Year’s run.

There’s another Substack essay in me somewhere about the ways my Swiftie-ism and my parents’ Deadhead-ism interact and speak to each other. Without having heard much of her music at all, Mr Spinach got deeper into the calculus of the surprise songs than many people I know. They checked TikTok every night checking for Happiness and Coney Island, the two songs they knew I most wanted. When my Eras Tour pre-sale came up on the worst possible day, when I was on a hiking holiday with almost no internet, my parents took all my login details and rode into battle together. It’s been gratifying to me to experience my own overwhelming setlist obsession, because it makes a part of my parents’ music-going lives feel more immediate to me. I like the feeling of our experiences reaching out to rhyme together across decades and genres. Maybe the way I felt standing in the pit when Hayley Williams came out on Wembley night 2 echo how my parents felt in the front row when Robert Plant appeared at a folk gig above a pub near Banbury.

In some ways, I think looking for accordances across the world as they heard it and the world as I hear it now primed me to specialise in modern reimaginings of the medieval. Not that my mum and dad are (quite) that old. But I’ve always spent quite a lot of my time discussing a world that doesn’t quite exist anymore. I’ve always been looking for paths into a semi-mythical past and ways to make it feel like ‘now’ again, to understand the people who lived there. I was very lucky to see Paul McCartney live last year, a true once-in-a-lifetime bucket list item. Then you’re looking at an older, somewhat bird-like man and trying to reconstruct in your mind what it was like to look at him in the 60s, to feel like liking him was dangerous, and something your mum wouldn’t approve of, rather than something your mum bought the tickets to. I pored over Peter Jackson’s Get Back documentary footage, trying to imagine myself into a vanished world.

Perhaps I sound a bit like Arthur Weasley asking questions about the muggle world when I talk to them. How would you say you felt about stamped addressed envelopes? What was it like waiting for shops to open so you could go there? What would you say spam, or bovril, or smash instant mashed potatoes, signified to you on a deeper level?

Before I loved medievalism and modern manifestations of pseudo-medieval worlds specifically, I loved looking for paths into making the past feel present again. Weirdly, the book that evoked the seventies in a way I felt able to ‘feel’ the most was Derf Backderf’s graphic memoir My Friend Dahmer. I don’t think this counts as a recommendation at all, and obviously this is a very painful and traumatic look at the factors that led Jeffrey Dahmer to become Jeffrey Dahmer, but large parts of the graphic novel are about what everyone else was up to while they failed to notice him. I’ve read it a few times, and every time, it does a good job of making you so caught up in someone’s late seventies teen life and whether they’ll really go to art school or not that you fail to notice warning signs going on around you. The air on your skin that particular late seventies summer feels distractingly real. I don’t particularly recommend anyone pick the book up for that reason, but there’s an interesting fact about my historical imagination for you.

But no matter how hard you work at a reconstruction project, you always feel a bit like Tony Soprano saying ‘I came in at the end’. A project that aims to capture something that’s either fading away or already faded will always be at least a little bit sad.

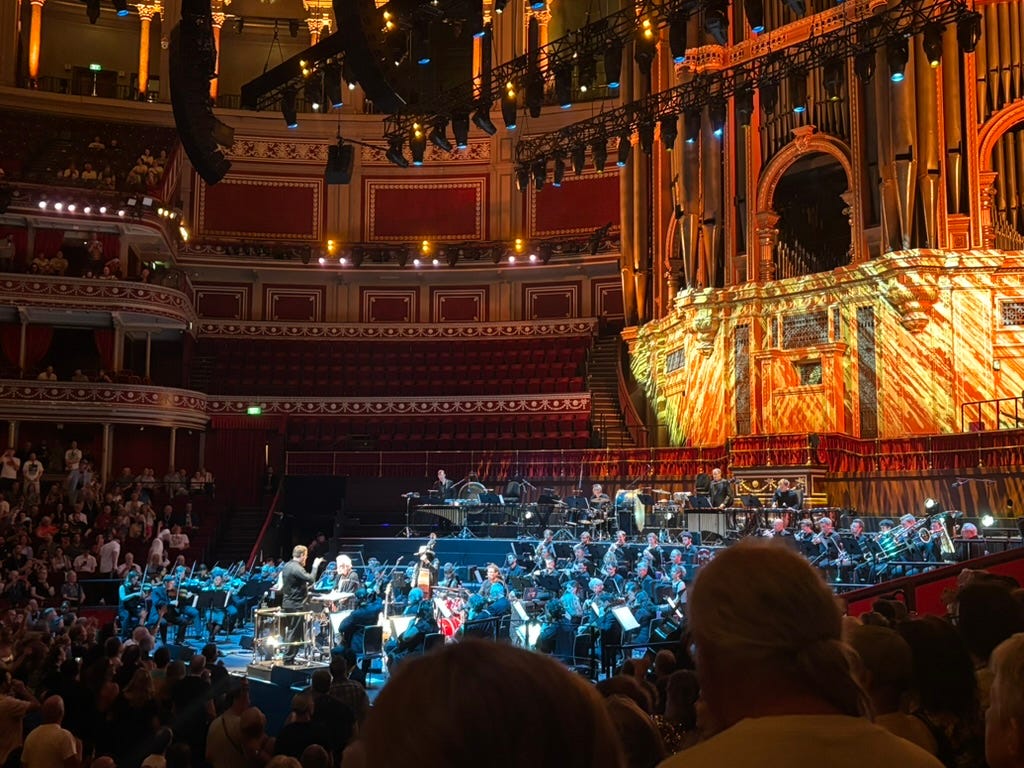

So on the longest day of the year, in the middle of a heatwave that wrecked me, I met my parents and a family friend at the Royal Albert Hall to see ‘Bobby Weir and Wolf Boys with orchestral backing’, except Bobby Weir is really Bob Weir, and really it’s the Grateful Dead, or the closest I’ll ever get. It was a meaningful experience to me in a way that’s genuinely hard to describe. It felt like catching a little bit of something as it flowed away.

Bob was always the most boyish-looking member of the band. When he stood next to Jerry Garcia they looked like a wizard and his boy-apprentice. Now Bob has grown a beard that rivals Jerry’s, pure white, with an enviable handlebar mustache. He could be an old-timey detective, or someone who drives a steamboat. Like I did with Paul McCartney, I try to trace how one turns into the other. I wonder what dress and grooming decisions Taylor Swift will make if I go see her live in thirty or forty years, how far I’ll ever see her as old or if I’ll always still feel young, still be at the Eras Tour. I wonder if she could pull off a handlebar mustache that well.

The crowd was a broad mix of ages, broader than I’d expected. There were quite a lot of americans, and I wasn’t sure if they’d travelled here specially or if the show had just flushed out all the California hippies who were in London anyway. One woman down the front of the stalls stood up to spin and throw groovy shapes. The camera operators in the shows I’ve watched on DVD always lingered on the spinning women, probably because they wore short skirts, so they feel like an important part of all the shows to me because those camera angles on the show are all I’ve got to build from.

It was an awesome show. Statistically, I don’t think many of my readers here like the Grateful Dead that much so I won’t do a full review here. Parts were deeply funky (Sugar Magnolia) and parts were probably longer than I needed (Terrapin Station Medley, which I’ve never liked at the best of times).

The song that made me actually cry was Brokedown Palace. It was the last song my parents saw Jerry Garcia sing, as the final encore at the last show they went to in 1995, just before he died. I reckon my mum must have been about two months pregnant with me when he died, so I’ve probably still got some cells that shared the world with him for a wee bit there. I don’t know much about how cells work but I hope that’s true. My dad found out that he’d died via a TV screen in a McDonald’s and he thought about Brokedown Palace, a song that says goodbye.

Fare you well my honey

Fare you well my only true one

All the birds that were singing

Have flown except you aloneGoing to leave this broke-down palace

On my hands and my knees I will roll, roll, roll

Make myself a bed by the waterside

In my time, in my time, I will roll, roll, roll

My parents said it felt weird to hear Bob sing it, because it’s so entirely Jerry’s song. I got a video of the first minute or so of it then I spent the rest of the song with my head on my dad’s shoulder. I never thought I’d see any version of this song live, even if it was sung by slightly the wrong person.

I don’t think being an only child is inherently better, worse, harder or easier than having siblings. I didn’t have any other kids to talk to on holiday as a child, and I talk too much, but no one ever moved my stuff or stole my food as a kid, so perhaps we’re even. Watching Brokedown Palace this weekend, I started thinking about the whole imagined world I’m heir to that no one else will share. There’s a country I’m a citizen of that will dissolve and leave me with a passport no one recognises one day.

It’s oversimplistic to say that being an only child automatically equals loneliness, now or in the future. A lot of people have siblings they hate, or siblings they have no strong feelings about. There’s no family relationship that gives you automatic insurance against loneliness. I’ve got a healthy, joyful relationship of eleven years and friends I’ve loved deeply and long enough I’m sure we’re family now.

I’ve always believed the truism that loving someone means learning a new language together. Eleven years with my boyfriend has built a culture of its own. Only we know what the correct answers to ‘wouldn’t it be nice to…’ and ‘it’s fun to stay at…’ are. When I insist we play Maisie Peters and Maisie Peters alone while baking with one friend, or when I watch Twilight for the hundredth time with another, we’re building linguistic and cultural worlds together and reinforcing their infrastructures. If I say to those friends, one day way in the future, that it would mean a lot to me if we made some Mexican food and watched a Grateful Dead show together on New Year’s Eve, I bet they’d do it. It wouldn’t feel exactly like it used to, but then, nothing ever feels like it used to. I wonder if we’ll all have grown white handlebar mustaches by then.

Going home, going home

By the waterside I will rest my bones

Listen to the river sing sweet songs

To rock my soulGoing to plant a weeping willow

On the banks green edge it will grow, grow, grow

Sing a lullaby beside the water

Lovers come and go, the river roll, roll, rollFare you well, fare you well

I love you more than words can tell

Listen to the river sing sweet songs

To rock my soul

I'm old enough to remember the Dead at their height, and I'm from the Bay Area, so ... they're just part of the background of my life?

My older brother didn't traipse around after them, but he did see them many times when they came through near him. He was SO pleased when I found a CD of what he considered the best show of theirs he ever saw and said it was just as good as he remembered.

Something about the Grateful Dead that I always adored was how specific in time the recordings and versions are. Like how the '77 and' 78 shows are so distinct from the '71/'72 while playing a similar set. Same thing with jazz recordings it's time unique despite often playing a small set of jazz standards. So cool you got to have your own unique Deadhead locket of time!