Birkbeck College: will I make friends at grad school, will I make my train, Waterstones cafe, the Scream

A very long response to a DM from a reader

I wasn’t going to write a long piece today. In fact I had an extensive to do list involving washing towels and working out what’s wrong with one of my house plants. Then I got a DM from a reader with a question following my last newsletter Academic journal access is a dog from hell. I talked a good bit in that essay (you should read it, it’s good) about the differences in my experience across the universities I attended for my undergraduate and masters degrees.

I went to Oxford for my first degree and Birkbeck College, University of London for my second one. If you’re outside the UK, or even if you’re inside the UK, there’s a good chance you’ve seen a bunch of movies set at Oxford and you’ve never heard of Birkbeck. It’s not a university that features on many aesthetic vision boards. I forgot to ask the person who commented if I could use their name, so I’ll call them Natalie. Natalie is looking at a Birkbeck part time masters degree on their horizon. Is there anything I think people should know? Do I have a take? Do I think they should run for the hills?

Looking at the DM I realised I had far too many thoughts to respond in the way Natalie was probably expecting, My thoughts settled into three questions I thought needed asking. I’ll tell you what they are in just a second, but first, an explainer for the people who aren’t sure what Birkbeck is or why someone might ask me this in a way they maybe wouldn’t for other universities.

Birkbeck College was founded in 1823 to provide university education to people who worked. Its teaching was all in the evenings so working people could access a ‘life of the mind’ that had never been available to ‘people like them’. It was the first higher education institution of its kind in the UK and the good it has done for working people is impossible to overstate.

And it’s still doing it. As well as people like me with full time jobs, I studied alongside mothers who could afford childcare in the evenings but not the day and people with disabilities who found block teaching in the same hours every night better. Everyone I tell about it says ‘I had no idea that was there but it sounds really good’ and I go, ‘yeah, it’s really good. I wish you knew about it’. Like Oxford, it’s a university that exists to honour a grand dream. The dreams are different - the dream of craftspeople walking to a philosophy lecture after a shift rather than the ancient ivory tower dream of scholars eating together in a college hall. I can dream multiple things, though, and I loved dreaming both.

The three questions to ask, then, are:

Is the teaching good?

Is the student experience good?

Will I wish I’d gone to a normal university?

Is the teaching good?

Yes.

Next question.

Well, there’s probably a bit more to say on that. Discussing the quality of teaching is always going to come down to what teachers you had and what subject you did. My MA was in Medieval Studies, which is a small, niche course that doesn’t exist anymore in the form I studied. Me telling you about the professors I had might be helpful if you’re also intending to study a humanities course in the English/history/etc world, but if you want to study accountancy I don’t know I have a single fact that will be relevant to you.

So with the caveat that this is just one experience, on a course that no longer exists, with a set of teachers who largely aren’t there anymore, I can tell you what it was like for me.

The teaching, in the most part, as close to perfect as I can imagine an academic experience being. If you’ve read The Sercret History and If We Were Villains and yearned for long, small-group seminars that evolve into pub sessions where world experts switch effortlessly between explaining Silk Road archaeology and mad anecdotes about a weird dinner party they went to, I had that. Not only that, I got it from friendly academics with clear professional boundaries who never made me or anyone else I knew feel uncomfortable in any way. Insofar as the names of prestige universities matter, I was taught in small discursive groups by graduates of Oxford, Yale, UCL and the University of Chicago. The teaching was personalised and tutorial-esque. It equalled or exceeded everything I got at Oxford in all respects other than the architecture of the buildings we were sitting in.

My boyfriend told me before I started the course that he worried no masters could possibly live up to the expectations I had for it, but the teaching staff I had blew that worry out of the water. A close friend who did a masters and a PhD at a much more Old And Shiny university told me the teaching sounded better than some of what she’d had.

The only exception to this was one module I took where budget cuts had affected the choice of modules on offer and I ended up taking a class from the ‘wrong’ historical period. I was a bit of a state at the time but looking back now, I have a lot of sympathy for the academic teaching that class. She was an early modernist stuck with five dissatisfied medievalists gazing up at her and not much time to rework her course material. We’ll talk more about budget cuts later on.

As well as the teachers, something I didn’t even know to look forward to when I started at Birkbeck was how much the student body would impact me. Birkbeck’s teaching model causes it to appeal to a wide range of people. Studying medieval studies, I’d be lying if I said it was a hugely diverse group in terms of ethnicity. But studying alongside people of different ages and backgrounds was fantastic and a really big part of what I loved. There were people there forty years older than me and their perspectives always took me by surprise, the product of education in other decades and countries than I was used to. Even just talking to people about how they managed their studies was useful and interesting to me.

So my answer on the teaching is that insofar as I have the ability to tell you anything about it, it’s spectacular. The staff on your course might be different or useless, but I can tell you what I can tell you, and my experience was amazing.

Is the student experience good?

This is a spicy question. In order to talk about this one, I think we have to confront a lot about what ‘student experience’ is.

Reading the kinds of books I’ve loved my whole life, and on social media, and in many people’s imaginations, ‘being a student’ means a specific set of behaviours and cultural signifiers. Students lounge on lawns reading fat academic texts, they sit up late drinking red wine and talking about poetry, they wear black turtlenecks and spectacles, they say ‘I’m so busy’ and they’re referring to scribbling til daybreak in the library. When they’re not doing that, they’re drinking, they’re throwing themselves into nightlife, they’re on sports teams, they’re in plays, they’re getting drunk with people they know from sports and plays. These imaginary students probably live in or near their university, they probably don’t have a paid job during termtime, and they have time for extracurricular activities and joining clubs and societies. These are ‘real students’, or what university policy folk might call ‘typical residential’ students.

Data from the UK as well as some other parts of the world shows that these students exist less and less with time. Birkbeck’s graduate students aren’t having this version of the student experience, but who is? More than half of UK undergraduates studying full time are also working at a paid job during term. More and more, students are commuting long distances to their university to study while living at home. The ‘student experience’ is increasingly failing to finish your reading because you were at work, and sitting on delayed trains. Not to mention, the ‘typical residential’ student was never everyone even back in the Good Old Days. Not that many people could afford to be The Secret History at the time Donna Tartt was studying or as she was writing it.

I met a small handful of students at Birkbeck who were living in student accommodation or privately rented flats in Bloomsbury while they studied. I also knew a handful of people who didn’t have a job or worked a more ‘student life’ type job, such as a couple of shifts a week in a bar. Some were retired, and therefore living a more ‘studentish’ life at a different age (these people were very cool and I want to be them when I grew up). In general, though, Birkbeck’s students were working, they were looking after kids, and/or they were travelling a good distance to study.

Did it feel like ‘really’ being at university? Yes in some ways and not in others.

Doing a part time masters at Birkbeck you’re on site at university one night a week. For a full time masters, it’s two nights a week. If you want to get to know people, spend more time with them, be more immersed in an academic culture, you have to get yourself in there like a parcel that’s nearly small enough to fit in a letterbox.

I think I did a good job of this and I’m really happy with the social experience I had, the community I was immersed in and how my ‘student experience’ turned out. Like the teaching point, that came down to a lot of personal factors that won’t be replicable for other people, but again, it’s all I’ve got to talk about. I’m a very naturally extroverted person and I was purposeful from the beginning about trying to meet people, get numbers, make group chats, invite people to things. If I saw an extra seminar or event advertised I’d turn up to it, in person or online, regardless of how relevant it was to my literal research or classwork. I booked myself in for extra seminars at the Institute of English Studies at Senate House, attended lectures on early modern travel narratives and Irish translation. I set up a reading group with a PhD student I met and I attended reading groups organised by other people. If you’re less naturally extroverted than me it might be harder, but I hope not impossible.

I came out of the degree with a good bunch of friends, most of whom still talk to me and some of whom read this substack (hi). Looking at the student body as a whole, I’d cautiously estimate a third of the people I had classes with were keen and up for socialising, a further third were into it in principle but had difficulties with childcare, travel or alarms set for five in the morning, and a final third weren’t really wanting to make friends and just wanted to get home.

Sometimes planning was chill and casual - ‘Want to go to the pub after the Senate House seminar?’ ‘You bet’. Sometimes it took a bit more organising, learning what days of the week someone had their kids and working out which Thursdays would match different work schedules. It was harder than at undergrad, when seeing my friends meant going six metres down a corridor to hang out with someone with no plans or responsibilities. I don’t mind it, though. I wanted to hang out with the people, and the people had a range of lives and stuff going on. I was older and more able to cope with a lively and packed google calendar. Having a diverse friend group of people with a lot going on in their lives means working around their stuff, and I’m glad I got to have the friendships that I got by doing that.

In the first year of my degree, my classes were 6.00-7.30 and it was convenient to pour into the pub after class ended. I went almost every week and had fantastic times. I had studenty times. I felt like a student sitting around in a bar being silly on a Wednesday, not a person with a job I was needed at in eight hours. That behaviour changed a bit in my second year when classes got longer. Only superhuman people are up for going to the pub at nine at night on a Tuesday after a three hour research seminar. So in my second year the socialising was a bit less vibrant, and I do wish the lengthening of classes to three hours hadn’t happened. Other people had other situations but I’d been in the office since 8am, used my lunch hour to finish my reading, microwaved dinner at my desk before heading to class, and then sat there for three hours trying to be clever. No one likes the pub that much.

I did keep being social in the second year. I had a study group who met at the British Library at weekends to write our dissertations. A wider group of us went to dinner to celebrate handing in our dissertations and toasted to It Being Over. It took some organising, and I think I had to work harder at it than I would have done at some other universities.

But students on the whole are getting busier and have more calls on their time than just arguing about Sartre on lawns. My three years at Oxford telling people how Very Busy I was working two shifts a week in a cafe and claiming to do more reading than I actually was is a vanishing version of what it means to be a student.

Increasingly, I don’t think it’s fair to hold universities to a standard that very, very few people can manage anymore. People at Birkbeck don’t have endless hours to argue about absurdist drama in the back rooms of smoky little coffee shops. But does anyone?

The social life was nice. Birkbeck’s campus is just across from a square that has a lovely little food market on Thursdays. Sitting in Gordon Square or Tavistock Square surrounded by cherry blossoms eating your sandwiches while the sun sets in the summer is amazing. The deliciously large Waterstones on the corner of Gower Street has a cafe that is truly one of my favourite in London, despite being associated with a chain bookshop, and serves a Christmas toasted sandwich that I would do unspeakable things to have access to all year round. I went there on my lunch hour with my friend Claire to cackle about our PhD applications and get cheese down my front. The Marlborough Arms pub is pretty good.

Socialising at Birkbeck can take many forms and survive many constraints. If you have to run to make a train after class, you’ll be in good company. If you want to hang out, you can hang out. The people I met were, in general, willing to smash our calendars together and seek times we could hang out. I might not be living in a perfect reenactment of The Secret History but I went to the British Museum with a friend on a Saturday morning to stare at early venetian maps while she explained her thesis ideas on medieval bondage and discipline. I’ve stayed out until I missed the last train home and had to wobble horribly onto the bus. I’ve had a good time.

Will I wish I’d gone to a normal university?

idk, maybe.

For a lot of people, including me, the option of going somewhere else wasn’t really there. When I was looking at Medieval Studies and Medieval Literature masters courses, there were three in London and Birkbeck was the only one I could fit round my job as well as the only one I could expect to study for less than £20,000. I’m happy with my choice but I also didn’t really have another choice.

Birkbeck as I’ve described it above sounds like a wonderful place and it was a wonderful place. My time lived up to all my expectations, fit well alongside my full time job, didn’t bankrupt me, introduced me to great friends, and got me into my dream PhD programme. Awesome. But we live in an odd time for British academia and I can’t honestly say the version of Birkbeck I studied at still exists.

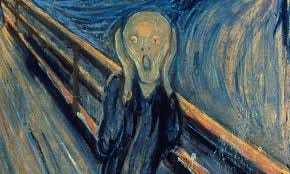

The funding position of British universities can best be summarised thus:

I could talk in detail about the impacts of tuition fees, trends in international student recruitment and changing pay requirements on universities as employers, but that’s not interesting to read about on Substack. If you stare into the eyes of the Scream, you’ll understand. All this uncertainty and all this screaming produces a lot of change. I started at Birkbeck in autumn 2022 and finished in autumn 2024, and the version of the university I attended already doesn’t feel like it exists anymore. Teaching hours have changed, the faculty is different, and the vibe is different. My friend Marie who studied the same stuff as me from 2020 to 2022 told me the way the course worked for me seemed unrecognisably different from what she remembered. From 2020 to now, the course I studied has changed name and outline twice. I am made really seriously sad by the brilliant medievalists Birkbeck doesn’t have anymore. Many of them haven’t been replaced, leaving a hole in the London landscape of excellent-quality affordable access to the past.

I should caveat this by saying that doing Medieval Studies, I am studying one of the most niche humanities pathways that exists in higher education. It’s me, classicists, and the critical theory mob twiddling our thumbs together when people ask us about employability statistics. If I’d done accounting or organisational psychology I’m sure I’d have very different things to say about my course and its future. Natalie, the semi-forgotten reader who asked me about my time at Birkbeck, didn’t tell me what course they were interested in. If they want to do mechanical engineering or economics then they probably don’t need to worry about this. The business school is doing great.

None of this is to say I think Birkbeck has got bad now. I continue to stand by it and recommend it, both the dream of what it aims for and the practicalities of what it delivers. My second year was different to my first year with longer teaching hours and less specialist staff, but I would rather have been there than anywhere else.

I want Birkbeck to keep existing. I think what it does is still worth having. Subject by subject and departmental budget by departmental budget, the situations of different courses are different and will get more different over time. I don’t know what it will look like in a few years, and indeed I don’t know what many universities in the UK will look like in a few years. Oxford, Cambridge and a handful of other ancient and ancient-ish universities have the particular privilege of knowing what their lives will look like in ten years, five years, one year. If you have an offer to study at Birkbeck in 2025, I reckon you should go. I’d go. I’d probably tell a friend whose situation I understood in more detail to go. I hope it goes well for you and I hope it goes well for Birkbeck.

Trying to imagine an image to end this essay, I just keep coming back to the image of Birkbeck’s first students, the craftspeople and tradespeople who got to listen to higher level science and economics lectures which had never been available to people like them before. I thought about them every time I went through the doors of the campus. I want to be at their institution, even if I’m a different kind of working person in a different age. I want to do them proud and I want their institution to preserve its individual magic, because a university like this should exist. It should teach classics, medieval studies and critical theory. It should teach them to stay-at-home-mums, fishmongers and emergency services personel (all people I met on my course). I want it to be there. I want as many people as possible to get to be part of it. I want it to survive.

I love this substack. Finding it has made me hate the algorithms a bit less. Just signed up for Birkbeck’s postgrad open evening.