an appetite and nothing more: Nosferatu and the horrid sensuality of rot

on the past refusing to stay dead under your shuddering fingers

I saw Nosferatu this week. I’m sure I don’t need to tell you I loved it, was surprised by it and also found it deeply disquieting. Everyone loved it, was surprised by it and found it deeply disquieting. Everyone said, ‘I didn’t know Lily-Rose Depp could do that’.

Many interesting things have been said about the film on a lot of fronts, and I don’t want to repeat things that have already been said better by people with larger audiences. There were two things I was particularly interested in Nosferatu, though, that I haven’t seen widely discussed. There’s something both very disgusting and very sensual about how every part of it is constructed. As an adaptation of an adaptation of an adaptation, and as a story about excavating layers of burial and dirt and trauma, it’s a film about excavating and uncovering, reaching into the dark depths of horrible holes. To my mind, it’s a film about how unavoidably sensual that uncovering process is, even when you don’t want it to be. It’s about the past refusing to stay dead under your shuddering fingers.

The act of uncovering is framed as sexual but not sexy. Nothing related to the sexuality is nice. Everything related to the film’s sense of sexuality is old, dirty, diseased. The oldness, dirtiness and diseasedness is so marked it can’t be ignored, and it gets more and more intense as the story progresses. I am a medievalist who specialises in looking at the ways post-medieval media constructs and imagines the idea of the medieval. What does the medieval do when we invoke it in later stories? What does a crumbling ruin in a gothic novel do? What does an illuminated manuscript in a Dan Brown thriller do?

In Nosferatu, the past does a lot, and it’s all sexual, covered in dusty and worms, and desperately icky. It’s never not horrible but it’s also always profoundly sensual. This is a story about running your hands over something nightmarish, but continuing to touch it. The story is rich in fluids that run over your skin, corrupted air breathed in and out, mud that congeals on your feet. We are never allowed to escape the sensuality of the experience. It’s a negative image of sexiness, asking you to touch all the things you least want to touch. It’s plague sores, blood coughed up and leaked from the eyes, a terrible ruined hand advancing across the screen to touch and be touched.

It is essential in Nosferatu that Count Orlok represent not only Ellen’s personal past but the medieval past. Castle Orlok is almost a caricature of a medievalist castle imagined in an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century gothic novel. In the castle, we get lingering close ups on handwritten text written with illuminated capitals and steep winding spiral staircases. In this and so many other texts, the Middle Ages is figured as a nightmarish dream-time from before everything we find comforting and regular about recognisable modern society gone together. The Middle Ages is the soupy cauldron of obscure pagan ritual and the first stirrings of customs that make sense. We often see the Middle Ages figured in fiction as a battleground between the rational and irrational, followed by the early modern period during which people started to be sensible and normal. A lot of horror texts (think of folk horror classics like The Blood on Satan’s Claw) figure the Middle Ages as a collective trauma we are all still recovering from centuries later.

So Nosferatu marries its psychoanalytic portrayal of Ellen’s own traumatic past to the widespread horror idea that the Middle Ages were a nightmare we all had in common. Count Orlok emerges from the Middle Ages into Ellen’s childhood into the modern city. He brings with him some of the horror ideas most commonly associated with the Middle Ages in all eras of English-language horror: rats carrying pestilence, bodies piled high in the streets, plague-fires burning on street corners, and also sexual repression, young female bodies in white dresses being preyed upon, intense bodily shame, being told you mustn’t mention the things that torture you. Ellen’s trauma is medieval.

Robert Eggers told The Guardian in December that he wanted his vampire to recall the earliest eastern European folkloric vampire stories. That’s pretty exciting for a medievalist to read, though I was disappointed he didn’t go with the earliest stories of each vampire starting out as an inflated bladder full of blood with a tube coming out of it that blows around the village like a tumbleweed trying to attack your legs. If you want to learn more about early Eastern European vampire-slaying narratives I really recommend the early chapters of Bruce McClelland’s Slayers and Their Vampires: A Cultural History of Killing the Dead.

The scene in which Nicholas Hoult follows the Transylvanian villagers out into the forest to watch them kill a vampire in its grave is one of the film’s most recognisably medievalist sequences. It is one of the parts Eggers was most excited to add into his story to make explicit his story’s grounding in medieval folklore. It roots his vampires in both a place and a time, and also very literally in the earth. As well as emphasising these vampires’ historicity, it makes them wormier and earthier. It tells us explicitly how vampires come out of the soil and how they go back in. It reminds us how many layers of dirt are on these grubby bodies and how many layers of grime we will have to feel our way through, risk getting on ourselves.

Out of the whole film, the single shot that most burned itself onto my retinas is, unfortunately, one I can’t find a screenshot of online. Maybe no one else loved it as much as me. After Aaron Taylor-Johnson opens the crypt door to visit (‘visit’) his wife’s body, there’s a long slow shot of his face in profile against one of the coffin lids. We see the plague sores on the side of his face for the first time and his death becomes, in narrative terms, completely inevitable rather than quite likely. He coughs and rich, slightly blue toned blood spills onto the coffin lid as he caresses it. There’s a slow, still moment where he keeps his head on the surface of the coffin and does not retreat from the blood. He might not even realise it is there. It’s both romantic and aromantic, sensual and anti-sensual. I was captivated by it at the same time as my stomach was sinking.

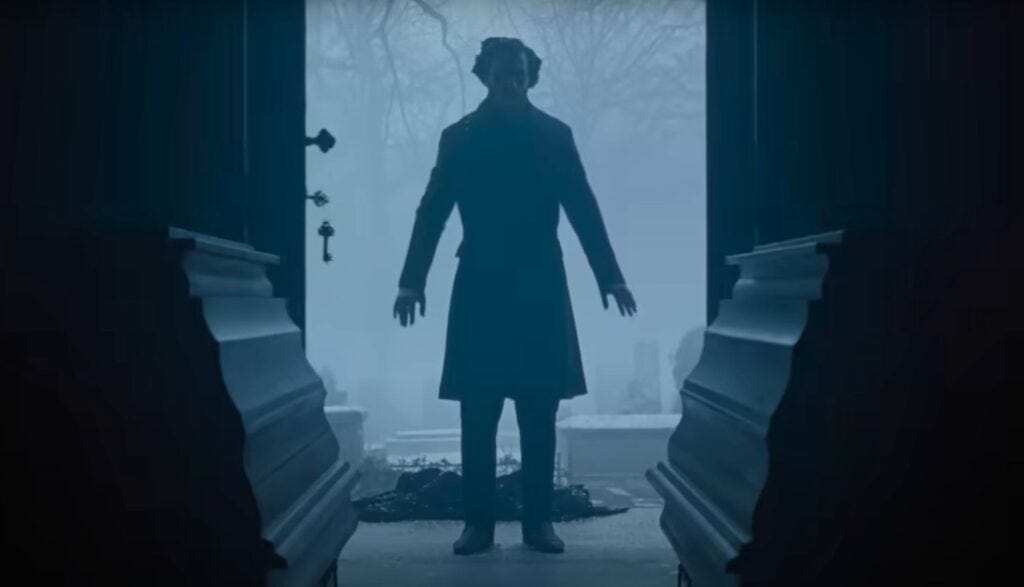

In this shot from a few moments before, which I could find on the internet, the mist behind his body is wondrously tangible. Watching this makes you imagine the mist touching and grabbing at you in the graveyard air, and the perceptible difference in atmosphere opening the door of the crypt. You can smell everything in this scene, can’t you? You don’t want to, but you can’t help but smell it.

Medieval things in film are often dead and intangible. You see flashbacks of people who used to live in a building, translucent ghosts in suits of armour or dusty books written by long-dead scribes. Few movies show anyone touching or being touched by a medieval body. Nosferatu insists on it. The past is rotting and diseased but still present to be touched and spoken to, and it demands to be touched and spoken to.

This insistence on bodily communion with the past that won’t let itself be buried is, in itself, very medieval. Obviously, I watched the film and thought about Dracula and my beloved 1970s Nosferatu. The 1970s film put emphasis in some very different places, though, and its vampire was both cleaner and more tender than this one. The other thing I couldn’t get out of my head, though, was an academic book chapter I read last year for my masters in medieval studies, on the unavoidably sensual relationship between corpses and the worms that eat them in medieval English poetry.

Let’s go there for a minute. Maybe you don’t want to but we have to go there. Isn’t that meta.

Karl Steel’s How Not to Make a Human: Pets, Feral Children, Worms, Sky Burial, Oysters (2019) is one of my favourite books I’ve ever read and one I recommend a lot to people who say they want to read more about medieval literature and thought. It’s lyrical, surprising, and unnerving. My favourite chapter, on worms, goes to great pains to emphasise how wormy medieval understanding of death was. It opens by quoting a widely-read Middle English Arthurian poem, the Awntyrs off Arthur, in which the ghost of Guinevere crawls dynamically with vermin. The idea of the beautiful Guinevere’s body infested with crawling consuming things is very foreign to the sanitised, retold Victorian Arthur that Tennyson gave us. Steel comments on this, and I wholeheartedly agree, that medieval presentation of death ‘is … enthusiastically committed to humiliating our pretensions to worldly dominance and bodily integrity’ (p.76).

The core of the chapter concerns the late Middle English poem ‘A Disuputation Betwyx þe Body and Wormes’. It’s a sexy little number that I couldn’t get out of my head during almost every scene of Nosferatu, more and more intensely in the second half of the film. The Disputation shows a dialogue between a woman’s body and the vermin that is eating her. They meet eyes as she rots. The result is more sensual than you might think. It’s a poem of sinking together, acknowledging the one-ness of worm and woman. If you’ve ever listened to Fade Into You and imagined being held so tight the barriers of your identity and selfhood collapse into a single romantic point of gravity, you might enjoy the Disputation.

Steel says:

… to immanence it adds a sexually charged, even sadistic interest in the flesh, a pack of talking worms, and an attempt to imagine an alliance between flesh and the worms that sprang from its own putrefaction. (p.79)

The poem is set during plague times, and its narrator enters a church to pray while escaping the disease.1 He encounters a fresh tomb with art depicting a beautiful woman in her healthy prime. He faints away, and we may imagine this is a response to her beauty or a signal he hasn’t escaped the plague as much as he hoped. He enters a dream world where he watches the woman and the worms that breed in her putrefying body. She mourns the corruption of her body and the worms remind her she was always destined for them. At the end of the vision, the woman accepts the truth of this, embracing the worms both philosophically and literally. While the poem looks forward to an eventual purifying of the body at the time of the last judgement, the image we are left with is not that cleansed glory, it is the worms. The idea of being cleansed is a long way in the future but the sensual and tangible reality of the worms is here to be touched and felt now.

Even though I read the book last year before I knew the Nosferatu remake existed, I can’t imagine anyone other than Aaron Taylor-Johnson entering that church now, running away from rot, running to rot. I imagine the cloud of blood exhaled from his mouth on the roof of the beautiful tomb. I imagine Lily-Rose Depp in her white dress with her arms open at the window ledge, calling to corruption with her purity, and I imagine her arms closing around Count Orlok’s terrible body, sealing and collapsing themselves together.

The film’s conclusion is a literal collapsing together of bodies. Purification requires making the decision to embrace rot. When we watch the men set fire to Orlok’s tomb, we know this ritual of destroying the rotting thing will not work. Orlok, Willem Defoe realises, cannot be destroyed that way. Only Ellen’s sacrificial ‘embrace’ of him through to the sunrise can enact actual purification, a purification that holds the rotting thing close rather than setting fire to it. When the bodies of Ellen and Orlok are found at the end of the story, they are put in context via the repeating of an old story about another maiden who sacrificed herself to Nosferatu.

So Ellen’s story settles into legend. We the audience know that this is one of many retellings and variations of a branching, sprawling story. We know disparate patches of eastern European folklore coalesced into early English-language vampire works like Polidori’s The Vampyre and Le Fanu’s Carmilla, and from here we got Dracula, and from here we got the first Nosferatu, and then the 70s one, and then this one. The versions of the story gather and converge like layers of dirt burying something old and terrible. With each incarnation the stories gather more weight and more legacy, remaining distinctively medievalist at the same time as answering to the concerns of new generations, concerns about what is horrific, what is sexy, and what is both.

This plot summary is paraphrased from Steel, though I strongly recommend reading the whole poem as it is quite short.

You WRETCHED bitch this is amazing. Thank you!!!

I watched it today, and loved both the film and this essay!